Most polls agree that the second round of the French presidential elections in April 2022 will most likely be won by the liberal Emmanuel Macron and a candidate from the extreme right, who could be Marine Le Pen.

In the 2002 presidential elections, the candidate of the traditional right, Jacques Chirac, and the far-right Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine's father, contested the last round. But this time there are two new factors that deserve our full attention.

2002 presidential election came after a Socialist Party government led by Lionel Jospin that carried out massive privatisations of public companies, creating a strong social unrest that weakened the left electorally. But in 2022 the elections will take place after five years of Macron's right-wing presidency, and an agenda of intense cuts that has been met with large-scale social mobilisations, including the "yellow waistcoats" rebellion. How is it possible that the left will not be able to channel this discontent and could suffer a resounding defeat?

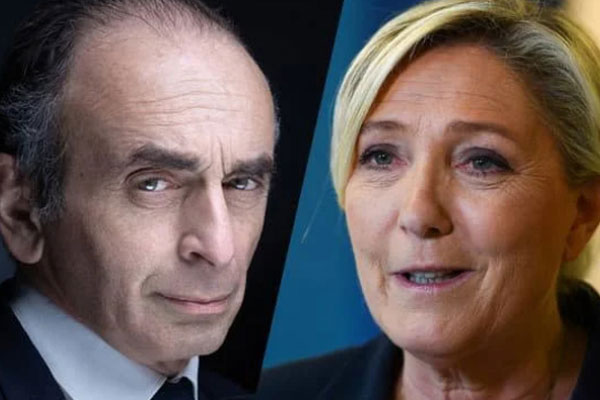

The dangerous rise of Éric Zemmour

The second factor that characterises the upcoming elections is that another far-right candidate, Eric Zemmour, has a chance of beating Le Pen and making it to the second round. This division on the far right, far from weakening it electorally, strengthens it. Its voting intentions have increased by almost 5 points since Zemmour and Le Pen have been competing for the same electorate.

Zemmour, a television journalist, has focused his discourse on what he calls French "national sovereignty", which is summed up in a programme of extreme economic nationalism and a ruthless attack on the immigrant population and refugees, with similar arguments of the anti-Semitic campaigns of Tsarism and Nazism. Zemmour embraces conspiracy theories that portray immigrants as an army, led by a hidden hand, whose aim is to start a civil war and destroy French civilisation.

Alongside this warmongering and racist message, he directs his hatred towards women and the LGTBI population, spreading the most repugnant reactionary lies, such as feminists wanting to "castrate men" or homosexuals adopting children to rape them.

With this kind of message Zemmour can reach 18% of the vote. A sign of the deep social crisis, which is hitting hard a rural and urban petty bourgeoisie that has always played an important role in the country's political life.

This petty bourgeoisie, whose narrow-mindedness Marx described so well, is caught between the fear of the working class and the revolution, and the uncertainty of losing its assets in the midst of a raging economic crisis.

In the 1930s, middle classes hit by the crisis became the social base of French fascism and Nazi collaborationism. In 1968, terrified by the great workers' and youth uprising of May, a large section of them mobilised in defence of property and order supporting the Bonapartist programme of General De Gaulle.

The 2008 crisis has once again hit the French petty bourgeoisie, both economically and in terms of their prospects for social advancement and national pride. These small landowners are directing their anger against the international financial order and against immigrants and refugees, who are a "burden" on public finances. That is why they turn their eyes to those who, like Zemmour, speak forcefully against "the elites" and offer the recovery of a supposedly splendid past. French Trumpism, with solid social roots, is bursting onto the scene.

The collapse of social democracy and neo-reformism

Much has changed since the 1930s, but the words of Leon Trotsky in Where is France Headed? are still valid today: "The desperate petty bourgeoisie see in fascism above all a fighting force against big capital, and believe that, unlike the workers' parties which work only with their tongues, fascism will use its fists to impose more 'justice' [...]. It is false, thrice false, to assert that petty bourgeoisie does not turn to the workers' parties because it fears 'extreme measures'. On the contrary: the lower stratum of the petty bourgeoisie, its great masses, do not see in the workers' parties anything but parliamentary machines, do not believe in their strength, do not believe them capable of fighting, do not believe that this time they are ready to carry the struggle to the end."

And history repeats itself again. The left's refusal to fight for a revolutionary alternative to capitalist decadence is what drives the middle sectors - and backward and desperate layers of the working class - into the arms of the extreme right.

Social democracy has ruled France for many years. In 1981, in alliance with the French Communist Party, Mitterrand won the elections with a programme that included major nationalisations and reforms for the working class. But that government was unable to resist the pressures of the bourgeoisie and renounced going beyond with anti-capitalist measures, pulling back on all the reforms initiated. Since then, the various Socialist Party executives have made policies indistinguishable from those of the right.

It was the failure of the PS-PC coalition that paved the way for the National Front, led at the time by Jean-Marie Le Pen. In 1986 it managed to enter parliament. Soon became an extra-parliamentary force again, but from then, it has been capable of getting a significant share of the vote and a strong municipal presence.

The large workers' mobilisations of the early 2000s, together with the anti-fascist campaigns, weakened support for the National Front. But the 2008 crisis once again offered it great possibilities. The growth of unemployment and the destruction of important industrial sectors by the relocation of French capitalists allowed the FN to make inroads into traditional areas of the left agitating for a chauvinist programme.

In 2011, Marine Le Pen displaced her father as head of the FN and attempted to detach the party from the more clearly fascist and racist traits of its past, even changing its name to Rassemblement National. His attempts to replace the traditional right in crisis with a touch of modernity brought him undisputed success: in 2017 she passed to the second round of the presidential elections against Macron. But in his shift towards "moderation" he left a flank open to his right, which Zemmour has exploited at a time of acute social polarisation after the pandemic.

The failure of the left coalition, and of successive socialist governments, also resulted in the electoral destruction of the traditional reformist left. The socialist candidate, Anne Hidalgo, the current mayor of Paris, has a 5% share in electoral polls and the communist candidate barely scrapes 2%.

In France, as in other countries, the 2008 crisis led to the emergence of an alternative to the left of social democracy, the France Insoumise, led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon. But Mélenchon, far from proposing a socialist programme, has adopted the rhetoric of "national sovereignty" and attacks immigration in the name of defending the social rights of native workers. Far from weakening the far right, this discourse pave the way for it.

Despite being by far the best placed of the left-wing candidates, the polls give Melenchon only 10% of the vote. Even if he manages to unite the votes of the rest of the left and the ecologists, he would barely reach 30% according to the polls.

The experience of the 1930s is clear. Only with a programme that puts in question the capitalist system and proposes a revolutionary transformation will it be possible to build a credible left with the capacity to confront the extreme right.