A Marxist View on Allied Air Warfare against German Cities 1942–1945

A few weeks ago, the British and US-American “Operation Gomorrah” – the destruction of large parts of Hamburg by area bombings lasting several days with devastating firestorms and over 30,000 civilians killed in July and August 1943 – was commemorated for the 80th time. This bombing campaign is considered to be one of the high points of Western Allied air warfare against major German cities in World War II, which was systematically carried out from 1942 onwards, devastated dozens of urban centres and cost the lives of several hundred thousand people.

Neo-Nazis and fascist elements of all kinds regularly abuse such anniversaries to spread their reactionary lies about an “Allied bombing terror” and thereby divert attention from the crimes of the Nazi regime. It was this fascist regime that started World War II in September 1939, and then covered the whole of Europe with misery and mass murder in order to ruthlessly enforce the interests of German imperialism. The extreme right remains silent about this fascist terror.

On the other hand, there are “left-wing” forces that not only oppose such propaganda of the neo-Nazis (which is correct), but actively defend the Allied bombings from 1942 onwards as a supposedly anti-fascist measure and underline this view with cynical slogans such as “Bomber Harris, do it again!”.

The truth is: the Allied air raids were, of course, not anti-fascist heroic deeds. On the contrary: they were an expression of criminal warfare and, moreover, largely useless – at least measured by everything that would have been helpful in an effective fight against fascism: Neither did they impair the Nazi Wehrmacht's ability to act militarily to any great extent, nor did they seriously destroy Germany's industrial potential. It is doubtful whether that was ever their primary purpose, as will be shown here. It is therefore that internationalist, revolutionary communists opposed the Allied area bombings already during the war – a position we defend.

The Second World War: An imperialist war for the division of the world.

A necessary starting point for dealing with the Allied bombing raids is the question of what characterises the Second World War of the years 1939 to 1945 as a whole. Contrary to what we learn in school to this day, this war was not simply a battle between “democracy” and fascism, but a global imperialist conflict involving states of different class character, each pursuing different goals.

The fundamental cause of this bloodbath from 1939 onwards was the imperialist competition between the bourgeois national states, which continued unabated after the end of World War I. The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky wrote in May 1940: “The present war, the second imperialist war, is not an accident; it does not result from the will of this or that dictator. It was predicted long ago. It derived its origin inexorably from the contradictions of international capitalist interests.” These contradictions manifested themselves, for example, in the Versailles treaty of 1919 dictated by the victorious powers of WWI, which burdened the German bourgeoisie – the German banking and corporate bosses – with heavy reparations payments and excluded them from important markets, raw materials and access to cheap labour. A redivision of the world at the expense of Britain and France, as had failed in 1914–18, was still on the agenda for the German ruling class. It was no coincidence that later – immediately after the German war successes of the summer of 1940 – one of the first measures taken by large corporations such as IG Farben or Carl Zeiss Jena was to draw up detailed plans for the “reorganisation of the European economy” in their own interests. Additional potential for conflict also arose from the collision of emerging powers such as fascist Italy or the Japanese Empire in East Asia with the traditional colonial powers and the ascending US over spheres of influence in colonial territories.

All the ruling bourgeoisies were in turn confronted with a powerful internal enemy: The revolutionary workers' movement, which had made attempts to seize power in several European countries after the end of World War I. Accordingly, they took it positively when the German bourgeoisie got rid of this danger in 1933 by transferring power to the Nazis and crushing the German workers' movement. The ruling capitalist classes of Britain or France were by no means “standing up for democracy” or fighting Hitler's Germany at the time. On the contrary, many of them expressed undisguised sympathy for fascism and their states openly cooperated with the Nazi regime. They ignored German rearmament or the remilitarisation of the Rhineland, for example, and Great Britain even signed a joint naval agreement with Germany in 1935.

This common internal enemy was matched by a common external one: the Soviet Union. The Soviet state had emerged from a victorious proletarian revolution in 1917; large landowners and capitalists had been expropriated there, the means of production were nationalised and a planned economy established. Regardless of its bureaucratisation, this completely different class character made the Soviet Union the enemy of all bourgeois states. Despite their competition with each other, they were united by their common fear of a spread of the property relations existing in the USSR to other parts of the world and of anti-colonial uprisings in the countries they ruled, which were supported by the USSR.

The contradictions of the allies. Imperialist war and proletarian revolution.

World War II began in September 1939 with the German invasion of Poland and the entry of Great Britain and France into the war against Nazi Germany. By the summer of 1941, the fascist Wehrmacht had overrun large parts of western, northern and south-eastern Europe – secured on its eastern flank by Stalin's pact with Hitler of August 1939, which was disastrous for the USSR and the communist workers' movement, that was controlled by the Soviet bureaucracy almost entirely.

The conditions of the war changed fundamentally when the Nazis and their fascist allies also invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. Now that a workers' state waging a defensive struggle against an anti-communist invasion force had entered the war, fundamental questions arose for Germany's previous opponents: on the one hand, they themselves had been waiting for more than two decades, since 1917, for the opportunity to militarily wipe out this first workers' state in the world and restore capitalism there (their expeditionary forces had failed to do so in the Russian Civil War); on the other hand, they found themselves in an imperialist war against the new invaders of the Soviet Union.

Although ultimately a joint “anti-Hitler coalition” was formed between the bourgeois states of Britain and the US on the one hand and the bureaucratically degenerated workers' state USSR on the other, the decision for this defensive alliance was by no means uncontroversial among the ruling classes of the Western powers. Two days after the German invasion of the USSR, for example, Harry Truman, then a US senator, commented in “The New York Times”: “If we see that Germany is winning we ought to help Russia and if Russia is winning we ought to help Germany, and that way let them kill as many as possible.”

For the Western powers, within the framework of the “anti-Hitler coalition”, one question always remained crucial: how to defeat Nazi Germany but at the same time protect private property and the market economy from anti-capitalist upheavals – whether through an expansion of the Soviet sphere of influence or through actual proletarian revolutions in Central and Western Europe. As early as March 1943, for example, Harry Hopkins, the closest adviser to US President Roosevelt, suggested that “Germany will go communist” if the Western Allies did not act quickly and decisively, and that something similar could happen in other European countries such as Italy, unless British and US troops were present at least in France and Germany ahead of Soviet ones.

Area Bombing and the Question of a Second Front

The decision to launch a systematic bombing campaign against the German civilian population also fits in with such considerations on the part of the Western Allies. It was made in February 1942: In the “Area Bombing Directive” of the British Air Ministry, the bomber command of the Royal Air Force (RAF) was ordered to fly missions that were to be explicitly directed against “the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular the industrial workers”. RAF Chief of the Air Staff Charles Portal specified only a little later that “the aiming points will be the built up areas, and not, for instance, the dockyards or aircraft factories”. It was not German industry that was to be targeted, but the residential areas of the industrial working class.

The method of area bombing on civilian targets was not new. The Nazis had already tested it in 1937 in the Spanish Civil War with the infamous bombing of Guernica and then brought it to sad perfection in May 1940 against Rotterdam and in November of the same year against the English city of Coventry. What was new, however, was its massive use by the British, whose air raids before 1942 had consisted mainly of precise strikes against military targets such as armament factories, railways, shipyards or battleships. Why was there such a reorientation at this time?

Practically from the first day of the German invasion of the USSR, Stalin had been pressing the Western powers to open a second front in the West to relieve the Red Army in its fight against the Nazis. For Britain and the US, large-scale area bombing was a welcome opportunity to “aggressively delay” such an invasion on the Western Front without demonstrating military inaction. In addition to concerns about their own military capacities, the decisive factor in this delaying tactic was certainly that a too rapid turnaround of the war in favour of the Soviet Union in the East or revolutionary uprisings of the working class, which a vigorous invasion of France or a consistent bombing campaign against German industry instead of the civilian population might have accelerated, were simply not in the immediate interest of the Western Allies.

“War on the Huts, Peace on the Palaces”

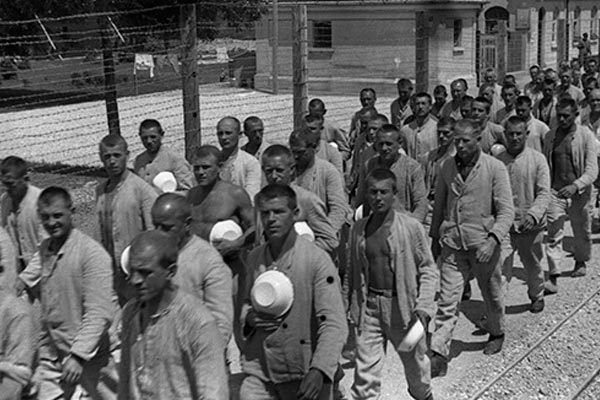

It is indeed remarkable how one-sidedly the Western Allied bombing war was directed against civilian targets such as the densely populated historical town centres of German cities. In contrast, objects important to the war effort such as industrial plants, power stations or submarine bunkers were hardly attacked to a comparable extent. In 1942/43, for example, targets of this kind never accounted for more than 20% of the total bombing load dropped – in all quarters except the fourth of 1943, the figure was only 10% or even less. Even in 1944/45, area bombing maintained a priority over attacks on industrial objects. The RAF also blatantly selected targets based on their susceptibility to fire rather than their military relevance to German warfare, which led to massive fire-bombing, primarily in inner cities.

Examples for this strategy can be found again and again. During its bombing campaign against Berlin between November 1943 and March 1944 the RAF, for example, carried out a total of 16 large-scale night raids against the Reich capital, which turned large parts of the inner city with its residential districts, but also some factories, into ruins. It is striking that the two important power stations, West and Klingenberg, which were responsible for 60% of Berlin's electricity supply and thus vital for the survival of local industry, were “forgotten” in those attacks – although their targeted bombing was explicitly being considered by the RAF back in 1940/41. War-critical objects were left out, just like bourgeois luxury districts in the surrounding countryside, while densely populated inner city areas with a majority of proletarians were bombed out beyond recognition.

This phenomenon did not go unnoticed by contemporaries. The Jewish architect Julius Posener, who fled Germany in 1935 to escape the Nazis and their anti-Semitism, reported the following after the end of the war:

“Many people told me about the extent of the destruction, and so when I came to Germany, after the reports of the large-scale attacks on German cities, I braced myself for a lot. But I must confess that my expectations were exceeded by the extent of the destruction...

In the suburbs (of Cologne) it looks a bit better; but even in the garden city of Marienburg every third house is in ruins, only that the ruins there are in the green. But if you go to the factory belt, especially to the east of the Rhine, outside Mühlheim, you will find many modern brick halls intact and working.

In the Ruhr I made the same experience: the workers' dwellings are destroyed, the suburbs are generally standing, and some villas are still occupied by their old inhabitants... The factories, however, the collieries and blast furnaces are working, except for certain special cases like Krupp in Essen... After the capitulation it was found that 20 percent of the industrial potential had been destroyed. That's a lot, but of the housing, 80 percent was damaged and two-thirds of it destroyed or almost destroyed.

Never have I seen a destruction that could so justifiably bear the name: War on the huts, peace on the palaces. One is tempted to see an intention behind this...”

A very calculated criminal strategy to slow down Hitler's defeat

Such an intention undoubtedly existed. As explained above, the warfare strategy of the Western Allies was at all times based on their most important goal of limiting the Soviet sphere of power in Europe and holding down revolutionary aspirations of the working class – especially in Germany. The struggle against the imminent “red danger” always remained the top priority for the ruling classes in Britain and the US. Hence, for example, their willing cooperation with old Nazis after 1945 to build up secret services and turn Western Germany into a frontline state against “communism” in the East. No bourgeois class of any nation had any interest in a real “denazification” of the German authorities back then. It has not taken place to this day.

The strategy of bombing the German civilian population must also be seen in this context. The British and US bourgeoisies deliberately used warfare that targeted the working-class neighbourhoods of major German cities (often with historically high communist influence) in order to “demoralise” the German working class and thus weaken a revolutionary potential. Their political calculations went so far that industrial facilities vital to the war effort sometimes seem to have been deliberately spared when it was feared that their too-rapid destruction might favour the Soviet advance in the East. The former Nazi armaments minister Albert Speer, for example, commented on conspicuous pauses in US air raids on the German mineral oil industry in autumn 1944 as a defendant at the Nuremberg trials by stating the following:

“We had the impression [...] that they were slowing down the pace of destruction in our country in such a way that their invasion and their plans of attack would run parallel to it, i.e. that our power of resistance in the East would be maintained until they had reached their stages in the West. This was the only explanation for us, because we knew that they had the means to do this and that they also had the economic experts who knew all the problems in detail. [...] I assumed that it was also of value to them that the Russians, in the event of a sudden collapse at our place, could not advance with their tank armies to the [...] extraordinarily important area at the Rhine.”

Speer was not the only one to express himself in this way. Even the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) occasionally let it be known in its internal reports that it was astonished that certain industrial facilities such as hydrogenation plants for the production of synthetic fuel for the Luftwaffe were not attacked by the Western Allies for a long time, although the importance and location of these objects must have been known to them.

The economic interests of US and British capital in largely undamaged industrial plants in a Germany soon to be occupied by them will certainly also have played a role. However, maximally effective warfare leading to the quickest and most comprehensive defeat of Nazi Germany on all fronts can hardly have been the intention behind the Western Allied bombing strategy from 1942 onwards.

German “Collective Guilt”: A Myth to Protect the Ruling Class

So if the Western Allied bombing war, through its one-sided focus on the civilian population and its consequent ineffectiveness, did not make a decisive military contribution to the rapid defeat of the Nazi regime, could it not at least be understood as a kind of “just punishment” for the German population, which after all had elected Hitler and supposedly enthusiastically supported the regime? Ideas of this kind are known as the so-called thesis of “collective guilt” and are partly to be found even on the political left.

The ones primarily responsible for the rise of the Nazis were the German bourgeoisie and the capitalist system. Important bank and corporate bosses had supported the Nazis with large donations even before 1933, because of their reactionary and anti-communist intentions. By no means did “all Germans” support Hitler: as late as the Reichstag elections in November 1932, the two workers' parties SPD and KPD together got 37% of the vote, while the Nazi party only got 33%. Among Marxist-oriented industrial workers, Catholic workers and even among the intelligentsia, the fascists remained largely isolated. They found support, on the other hand, among the petty-bourgeois middle classes, the peasantry, the lumpenproletariat and sectors of the big bourgeoisie.

After the Hitler regime was finally established in the spring of 1933, it was only able to stay in power for 12 years because it unleashed a veritable civil war of open terror against the working class and its political organisations: between 1933 and 1939 up to 600,000 people were imprisoned in Germany for political reasons, and in the spring of 1943 there were about 200,000 German political prisoners in concentration camps. Tens of thousands of Social Democrats and Communists were murdered by the Nazis. Even when illegal political resistance was almost impossible during the war years, SS offices reported workers' unrest in large factories from time to time for economic reasons.

Obviously the Nazis were able to impose themselves and crush the working class, as a result of their paralysis due to the disastrous role of their leaderships, both the SPD and the KPD, incapable of standing up to Hitler with a revolutionary policy and a united front. The SPD itself trusted to be able to confront the Nazis through the State apparatus itself, through the bourgeois democracy of Weimar, through the arch-reactionary Junker Hindemburg, President of the Republic who finally appointed Hiltler as chancellor. This State apparatus not only did not defend bourgeois democracy, but also put itself fully and almost entirely at the service of Hitler.

The thesis of "collective guilt" absolved the bourgeoisie and its capitalist interests, as well as the State apparatus (police, military, judges...), of their responsibility for fascist rule and instead placed this responsibility on the broad masses of the population. In this way, the real criminals could be concealed and the heroic anti-fascist resistance of the proletariat, which had paid a high price in blood, could be consigned to historical oblivion. This was in the interest of both the defeated German bourgeoisie as well as the ruling classes in Britain and the US.

The area bombings of the workers' residential quarters could also be justified in this way. But these bombings could, of course, not contribute to the fall of fascism – because they hit the wrong ones: Not pro-fascist industrialists like Thyssen, Kirdorf or Borsig in their villas, but the workers in the proletarian quarters, who had always been predominantly left-wing. Cynically – and precisely in order to nip potential revolutionary developments in post-war Germany in the bud – British and US air raids thus destroyed precisely those areas of public life – the urban ones – in which resistance networks had been most likely to form since 1933. The negative effects of the bombings on illegal political work on the ground were repeatedly reported by anti-fascist resistance fighters after the end of the war.

Revolutionary Communists against the Allied Bombing War

It is to the great credit of the forces of authentic, revolutionary Marxism – grouped in the Fourth International during World War II – that they almost alone at the time held aloft the banner of consistent internationalism and condemned the Western Allied bombing of German cities as a crime against the German workers.

These revolutionary communists had no illusions in the supposed “anti-fascism” of British and US imperialism. Unlike the Stalinist leaderships of the official Communist Parties, they did not subordinate themselves to the USSR's foreign policy alliance with imperialism and therefore rejected both participation in chauvinist, “anti-German” propaganda (such as the nationalist slogan “À chacun son Boche” [“Let each one kill a German”] in the French Resistance) and a justification of the area bombings. Instead, they relied on proletarian revolution in Germany and Europe as the most effective method of defending the USSR and defeating Hitler.

As part of their illegal work in the occupied countries – for example, with the newspaper “Arbeiter und Soldat” (“Worker and Soldier”) among Wehrmacht troops in France – they took a public stand against the Allied bombing of German workers' neighbourhoods. The Provisional European Secretariat of the Fourth International, for example, proclaimed in a resolution in December 1943:

“The bombardments of German cities follow one another in quicker succession and with growing intensity. Throughout the winter, thousands upon thousands of German and foreign workers are suffering the cruel consequences of the imperialists' air war. Whole cities are wiped out within a few hours. [...] [Anglo-Saxon imperialism] is also consciously mixing up the working classes of Germany with the German imperialist bourgeoisie and its political tool, the present Hitler regime. [...] [It] seeks by its air terror action against the German population and its racist 'antiboche' propaganda to demoralise the German proletariat, to break faith in the internationalism of the working class and to position the foreign proletariat against their brothers of Germany, to break the revolutionary wave [...].”

The militants of the Fourth International defended crucial Marxist class positions with statements like this. We can still learn from their method today.

Against fascism: Socialist revolution and proletarian internationalism

The Nazi regime was a bitter enemy of the international workers' movement. It had to be crushed and militarily defeated, and its capitalist breeding ground overcome, in order to permanently banish the fascist danger. Workers and communists in illegality, anti-fascist partisans throughout Europe and the Red Army of the Soviet Union waged a life-and-death struggle for years to achieve these goals.

Great Britain and the US were also interested in a military victory over Nazi Germany – but mainly in order to eliminate an imperialist competitor, not to eradicate fascism once and for all, for which its capitalist basis would have had to be eliminated. This is precisely what the imperialist Western powers did not want. On the contrary, for them the maintenance of capitalism and the prevention of socialist upheavals in Germany and Europe were central. Fascist rule was never a fundamental problem for them, but often a means to an end, as their long-standing cooperation with Franco's Spain and comparable dictatorships proves. Their war policy reflected this interest.

The British and US area bombings of German cities in World War II were therefore not motivated by anti-fascism and their aim was obviously not to liberate the German workers from the Nazi regime as quickly as possible. Instead of consistently eliminating Germany's armament potential or promoting revolutionary uprisings against Hitler from below, the Western Allied bombing war targeted the civilian population: in 61 German cities with over 100,000 inhabitants, it destroyed about 3.6 million homes, made 7.5 million inhabitants homeless and killed over 400,000 people. Of course, these figures bear no relation to the crimes committed by the Nazis. But that does not change the fact that they too are testimony to an imperialist warfare that sought not the self-emancipation of the workers but the safeguarding of capitalist rule against them.

Moreover, bombing the civilian population on such a massive scale had a delimiting effect: it could subsequently be repeated under different conditions in imperialist wars over Japan, Korea and Vietnam – with the terrible climax of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

Those who want to fight fascism consistently must have no confidence in capitalist states, for whose bourgeoisies fascist rule always remains an option and whose military strategy corresponds to their class character, which is why they rely on criminal methods such as the indiscriminate, large-scale bombing of workers' neighbourhoods. What is needed instead is the struggle against the social basis of fascism – the capitalist economic and social system. Only the revolutionary elimination of this system through the conquest of power by the working class and the establishment of a worldwide socialist order can guarantee humanity a peaceful future without fascism and war.